I begin with two incidents that illustrate two current and significant threats to our modern understanding of religious freedom. These threats come from opposite directions, but they offer touchpoints for asking what religious freedom should mean in the days ahead.

First, the U.S. Supreme Court has now decided that same-gender couples have a constitutional right to marry. The Court’s majority opinion nonetheless emphasized that churches and religious people may “continue to advocate” and “teach” their view that “by divine precepts, same-sex marriage should not be condoned.”1 Yet it remains to be seen whether the right to “advocate” religious beliefs will also protect conduct based on the “free exercise” of those beliefs against claims of discrimination. As Mr. Chief Justice Roberts said in dissent, “the First Amendment guarantees” not merely religious speech but also “the freedom to exercise religion. Ominously, that is not a word the majority uses.”2

Therefore, the Chief Justice believes there will be difficult future conflicts between “the new right to same-sex marriage” and, for example, the desire of “a religious college [to provide] married student housing only to opposite-sex married couples, or a religious adoption agency [that] declines to place children with same-sex married couples. Indeed, . . . the tax exemptions of some religious institutions [may be] in question if they [oppose] same-sex marriage.” So the gay marriage case gives a new urgency to longstanding questions about the relative priority of religious freedom when it is pitted against other constitutionally protected interests.

The second incident raises quite a different question. A few years ago while on a Church assignment in one of Sweden’s largest cities, I accompanied the local LDS stake president on a visit to meet the city’s mayor. I assumed the mayor would already be acquainted with our Church, because his community included more than a thousand Latter-day Saints, and we had built some large chapels there. We introduced ourselves, told him about his good citizens in our congregations, and then presented him with a framed copy of our Church’s Proclamation on the Family, along with a small sculpture of a young married couple reaching out to their toddler.

Holding the Proclamation in his hands the mayor said soberly, “For the last two days, I’ve been trying to help protect a young immigrant woman in our city from being killed by her father because he says she violated the family’s religious moral code.” Then in a gesture of rejection, he tossed the Proclamation on the table between us and said, “If that’s what you mean with your religious family proclamation, I want no part of it.”

We told the mayor that we completely shared his shock that any person in a civilized society would descend to violence in the name of religion or family honor. Yet I was truly surprised that this otherwise intelligent man seemed ready to equate all religion with the claims of religious motivation behind an extremist’s murderous attack on his own family—and perhaps, by implication, attacks in other countries by terrorists claiming to have religious motives. Was he really unable to distinguish those horrific evils from the civilized religion that has played such a crucial role in creating Western culture’s understanding of human dignity, human rights, and democratic society?

It is true that unspeakable atrocities are now being committed in the name of religion—some of them similar to the barbaric violence inflicted by such secular philosophies as Facism and Communism. That makes the present moment an even more appropriate time to remember and to clarify the kind of religion that has given the entire Western world its core sense of human freedom—not just religious freedom, but all political and personal freedom. That civilized sense of religion is so essential to our history, to our constitutional theory, and to the sustaining of successful democracy that we must never let it be confused with radically evil movements that brazenly carry religious flags today.

Nor should we let our honored Western tradition of civilized religion be confused with actual bigotry regarding sexual orientation. The historical sweep invited by this conference will give these issues a much needed and long-term perspective.

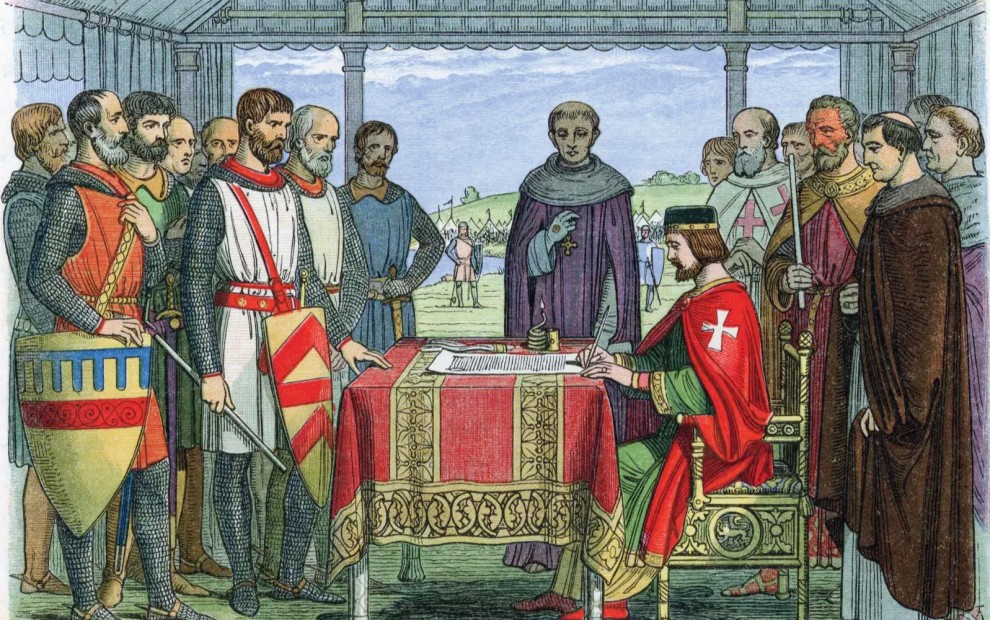

We celebrate today what happened exactly 800 years ago this week at nearby Runnymede, when King John and a group of rebel barons agreed to Magna Carta. That great charter has since been called the “cornerstone of English liberties”3 and “the greatest constitutional document of all time—the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot.”4 Magna Carta was both mediated and drafted by Stephen Langton, the wise Archbishop of Canterbury, who viewed it as an opportunity to create “a biblical, covenantal kingship in England,”5 based on the Old Testament pattern in which King Saul covenanted with God and with the people that he would observe the written laws of the kingdom—and all Israel shouted before Saul the now familiar prayer, “God save the king.”6 Magna Carta can thus be understood “as having avowedly religious origins,”7 making it what some have called “the masterpiece of Christian liberty.”8

The charter’s early years, however, were not at all promising. It never had the force of law, neither the king nor the barons kept their commitments to it, and instead of bringing peace it resulted in civil war. Moreover, the Pope annulled the charter soon after it had been adopted. And executions for heresy continued in England for another four hundred years—partly because the charter gave no protection at all to freedom of individual belief or conscience, even though its first article did grant freedom to “the English Church.” Nonetheless, in spite of these ragged beginnings, Magna Carta had planted the seeds—the powerful ideas—of what would become the very foundation of the rule of law: being governed by laws, not by men.

These seeds sprouted four centuries later in England and soon burst fully into bloom in America. In forcefully opposing the divine right of kings claimed by the Stuart monarchs in the 17th century, the celebrated jurist Sir Edward Coke relied on Magna Carta as “the principal ground of the fundamental laws of England.”9 Political thinkers like John Milton expanded the charter’s central concept of liberty to include individual freedom of conscience, religion, and speech as inherent, even God-given human rights—ideas that would shortly be adopted as guiding principles by the American founding fathers.

Milton’s insights help explain the source of religious freedom, an issue that takes on increased meaning when we ask why religion has such high priority among the principles that guide a democratic society. That priority arises not just because churches should enjoy freedom from government interference, but because freedom for religion in a more personal sense is the fountainhead for nurturing the core values of personal and civic virtue that allow democracy to thrive over time. For example, Milton believed that “by being created in God’s image . . . each person has something of the ‘mind of God’ within him, a ‘conscience of right reason’ that gives him access to divine truth . . . and a will and capacity to act on that knowledge.”10

Milton also articulated the need for freedom of speech and a free press in order to maintain the marketplace of ideas on which a free society depends. As Professor John Witte said, Milton’s “theory of freedom of speech was at heart his theory of freedom of religion writ large. Freedom of the religious and Spirit-filled conscience” is in reality “freedom of the rational and inquiring mind. The devout . . . parishioner in the pew” is also “the good and solid citizen on the street.” Effective self-government is truly made possible by “the open marketplace of true and false ideas competing in the public square.” And this process proceeds from the premise that “God’s truth” will “triumph once freed from human errors and controls,”11 if the marketplace remains stable enough to work.

The ideas of Coke, Milton, and other European writers then crossed the Atlantic to put sharp intellectual arrows into the quivers of America’s founding fathers. Thomas Jefferson agreed with Milton about the source of human rights: ”We hold these truths to be self-evident,” he wrote in the Declaration of Independence, “that all men are created equal and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” He also said that “governments are instituted among men” precisely in order “to secure these rights.” In other words, the human rights hinted at by Langton, described by Milton and others, and included in the American Constitution’s Bill of Rights existed prior to the state’s existence. They were derived directly from God, not from the state, and the state’s role was and is to protect those prior rights.12

Some years ago in South Africa the late U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy used language very familiar to Latter-day Saints when he echoed Milton and Jefferson by saying that “the essence of human rights thinking is that each human being is the precious child of God.”13 Building on this idea, English Judge Sir Rabinder Singh has said that even though “belief in human rights does not have to depend on . . . belonging to any faith system,” still, “throughout history the concept of human rights has been shaped and influenced by those” whose religious faith taught them “that we are all the children of God and members of one human family”14 and that, therefore, “every human being is a brother or sister” and that “ethical living requires universal love towards others.”15

Speaking of being children of God, modern scripture gives the members of our Church a unique understanding about a divine role in founding the American Republic. In 1833, the Lord said that He had “established this [United States] Constitution . . . by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose.”16 No wonder Wilford Woodruff would later say that the “men who laid the foundation of this American Government and signed the Declaration of Independence were the best spirits the God of Heaven could find on the earth.” 17

The approach of the American Founders to the subject of religious freedom was especially important to Latter-day Saints, because if the U.S. had adopted the English system, the Lord could not have restored his Church. Why? Because even though religious liberty was clearly emerging there, England still allowed only one official state religion, as did virtually all other countries where a new Church might have been organized. And prior to U.S. independence in 1776, nearly every one of the American colonies also had a state religion. But by Joseph Smith’s time in the early 1800’s, new winds of religious freedom were blowing—and it was finally lawful to organize a completely new Church in the State of New York.

Steven Waldman’s recent book Founding Faith: How Our Founding Fathers Forged a Radical New Approach to Religious Liberty18 pays special attention to the lives and thoughts of Benjamin Franklin, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and James Madison--the five founders who had the greatest influence in developing the American vision of religious freedom embodied in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

As Waldman summarizes, “the Founding Faith . . . was not Christianity, and it was not secularism. It was religious liberty—a revolutionary formula for promoting faith by leaving it alone.” Despite their individual differences on many related questions, the five key founders generally believed deeply that God intervenes in the affairs of humankind, and they all “felt that religion was extremely important . . . to encourage moral behavior and make [their new nation] safe for republican government.”19 Thus they believed that religion would help their free government thrive “by keeping officeholders honest and voters virtuous.” 20 As John Adams put it, “It is religion and morality alone which can establish the principles upon which freedom can securely stand. The only foundation of a free Constitution is pure virtue, and if this cannot be inspired into our people, they may change their rulers and the forms of government, but will not obtain a lasting liberty.”21

And what did the Founders mean by “religion”? Each had his own distinctive approach, but Jefferson’s was typical, especially as he mellowed with age: To live a life worthy of salvation, Jefferson wrote to a friend, “Adore God. Reverence and cherish your parents. Love your neighbor as yourself, and your country more than yourself. Be just. Be true. Murmur not at the ways of Providence.” Such a life is “the portal to [a life] of eternal and ineffable bliss.”22

These five founders all had serious reservations about the organized Christian churches of their time, and they disliked the tyranny they saw being imposed by some state religions in the individual colonies. So, in a process that I believe was attended by divine inspiration, they finally came to a unique, shared approach based on three key principles: First, religion is essential to the flourishing of a democratic society. Second, church and state should be separated, because that separation spawns a more authentic religious belief. And third, “God gave all humans the right to full religious freedom.” 23

The American founders understood the personal and social value of genuine religious faith so clearly that they resisted the temptation to establish an official state religion. They knew of themselves that requiring faith doesn’t make it real faith.

The general trend of the last two centuries shows that the American founders were correct in believing that their approach would lead to more religious liberty and to more genuine religious practice. In 1776, 17% of the US population claimed membership in a church. By 1850 that percentage doubled to 34%,24 and today it has more than doubled again, as 76% of Americans now say they are affiliated with a Church.25 Gallup surveys for the last twenty years tell us that well over half of the U.S. population have consistently said that religion is very important in their lives.26

Of course, the gap between how we believe and how we actually live is always a challenge. In one recent U.S. poll, 77% said they believe religion is now losing influence, but ten years earlier, 71% thought religion was increasing its influence.27 And a 2015 Gallup poll found that Americans’ confidence in organized religion has hit a new low. In the mid 1970s about 70% had high confidence; that figure is now 42%. Public confidence in most institutions has been declining for years, but organized religion has also slipped from being the most trusted institution to being the fourth most trusted—behind the military, small business, and the police.28

Still, compared with other developed nations, Americans “believe in God more, pray more, attend worship service more” and are “the most religiously vibrant nation on earth, not despite separation of church and state—and religious freedom—but because of it.”29

Moreover, this pluralistic brand of religion with its many churches has blessed society. Over the years most American social reform movements that improved the status of the disenfranchised or the maltreated were fueled by religious faith. For example, ending slavery and child labor, improving working conditions, establishing public schools, a social safety net, and the civil rights movement “were all driven in large part by people of faith.” 30

This historical evidence affirms that 800 years ago, Archbishop Stephen Langton indeed placed the spark of civilized religion into Magna Carta, even though it took several centuries for that spark to ignite fully and then to burn as brightly as it does today: Langton lit an “inextinguishable torch, handed on from generation through generation to our own: the axiom that [civilized religion] is committed to the principled and active betterment of society as a whole.”31

At the end of Steven Waldman’s book about the founding fathers, he titles his last chapter, “Friends in Heaven: the founders end their spiritual journey and prepare to continue the conversation in the next life.” For example, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both former U.S. Presidents, had once been good friends before becoming political enemies. In their later years they renewed their friendship, exchanging thoughtful letters for over ten years.

In 1823, three years before they both died, one of Jefferson’s letters to Adams imagined “the two of them standing at the windows of heaven, blissfully reminiscing and peering below, without the burdens of responsibility. ‘You and I,’” Jefferson wrote, “shall look down from another world on these glorious achievements to man, which will add to the joys even of heaven.’”32

Jefferson also wrote in 1818 when John Adams’ dearest friend and companion Abigail had just died. Listen to Jefferson’s belief about relationships beyond the grave—perhaps the prospect of eternal love and even eternal marriage: “Although mingling sincerely my tears with yours, will I say a word more, [even though] words are vain, but it is of some comfort to us both that the term is not very distant at which we are to deposit . . . our sorrows and suffering bodies, and to ascend in essence to an ecstatic meeting with the friends we have loved and lost and whom we shall still love, and never lose again. God bless you and support you under your heavy affliction.”33

Then the Lord extended one last stamp of heavenly approval to Adams and Jefferson, those leaders among the “wise men whom [He] raised up” to prepare the American Constitution. On July 4, 1826, John Adams was on his deathbed at the age of 90, while the country was celebrating Independence Day. Among his last words, Adams remarked about his old friend and competitor, ”Thomas Jefferson survives.”34 But in fact, Jefferson had died earlier that same day in Virginia at age 82. What a striking little miracle, that these two intellectual and spiritual giants would both have died fifty years to the day after each had signed the Declaration of Independence, of which Jefferson was the principal author.

As David McCullough wrote in Adams’ biography, “That Adams and Jefferson had died on the same day, and that it was, of all days, the Fourth of July, could not be seen as a mere coincidence: it was a ‘visible’ manifestation of ‘Divine favor,’ wrote [Adams’ son] John Quincy in his diary that night, expressing what would be said again and again everywhere the news spread.”35 The Lord did watch over these men.

Because of events that occurred soon after the 1877 dedication of the St. George Temple—the temple where my wife Marie and I recently served—President Wilford Woodruff had a special relationship with the American founders; but that is a story for another day. Suffice to say, it wouldn’t surprise me to know that John and Abigail Adams, or George and Martha Washington and the other couples among the founders have already learned how their marriages could become eternal ones.

One of the most compelling witnesses about the effect of civilized religion on democratic society is found in Democracy in America, written by Alexis de Tocqueville in the 1830’s. Tocqueville had visited the U.S. in an effort to understand why democracy flourished better there than elsewhere, including in his native France. One of his central findings was about the role of what he called free or “voluntary associations,” such private “intellectual and moral associations,” as churches, families, and other groups.

Tocqueville found that these local associations sustain democracy by teaching each generation the values, attitudes, and skills that equip people for self-governance—the personal and educational pre-requisites of a functioning free society. That may seem like a simple, obvious process, but it really isn’t—and it doesn’t automatically happen whenever a country calls itself a democracy. But when these associations do function, they teach people to cooperate for the larger good, not just to pursue self-interest.

In a free-market economy and a free society, if people only look out for themselves, who protects the community’s social interests? In Tocqueville’s words, “Not only [does unrestrained] democracy make men forget their ancestors, [it] also clouds their view of their descendants and isolates them from their contemporaries. Each man is forever thrown back on himself alone, shut up in the solitude of his own heart.”36

From watching American society function successfully, however, Tocqueville saw that the best way to bring civic virtue to otherwise self-centered attitudes was through teaching each generation voluntarily to cultivate personal “mores” or “customs”—what he called the “habits of the heart” that lead people to obey the unenforceable. Democracy cannot sustain itself unless people obey the law because they choose to, not just because they have to. And he saw precisely that kind of teaching and learning taking place in American churches, families, and other voluntary associations.

Religion played the primary role in this process, not by controlling laws, but by directing the personal “mores” or habits that regulate “domestic life,” thereby helping regulate society. In Tocqueville’s words, “The great severity of mores which one notices in the U.S. has its primary origin in [religious] beliefs.”37 “While the law allows the American people to do everything, there are things which religion prevents them from imagining and forbids them to dare. Religion, which never intervenes directly in the government, should therefore be considered as the first of their political institutions.” Religion “singularly facilitates their use” of liberty.38

Therefore, he concluded, those who “attack religious beliefs” are obeying “the dictates of their passions, not their interests. Despotism may be able to do without faith, but freedom cannot…How could society escape destruction if, when political ties are relaxed, moral ties are not tightened? And what can be done with a people master of itself, if it is not subject to God?”39

Some modern writers have used the term “mediating institutions” to describe the associations Tocqueville was talking about.40These institutions “mediate” between the lonely individual and society’s “megastructures”—the government, giant corporations, labor unions, and now the huge media, information, and entertainment industries. In a free society, it is not the place of the megastructures to give personal meaning to our lives. Our Constitution consciously prevents the government from assuming that role. In totalitarian states, by contrast, the government gladly controls personal values and meaning, telling its citizens not only what to do, but what their very lives mean.

In a free society, the megastructures are simply a means to help individuals pursue and develop their own chosen purposes. But today’s mass society can create the impression that responding to a constant barrage of advertising, political correctness, or the herd instincts of the social media are ends in themselves. Too many people these days live in a value vacuum that is so distracting and noisy that they are not aware of how aimless or pointless their daily walk might actually be. We can too easily mistake all the noise for applause. But as Elder Neal A. Maxwell once said, the laughter of the world is just loneliness trying to reassure itself.

In a strong democratic society, as Tocqueville observed, the individual develops his or her sense of life’s meaning and purpose primarily from religious associations and stable family relationships. These are the principal value-generating and value-maintaining associations that teach and foster the greatest fullness of life. Some of those values are bedrock and universal, such as honesty, self-discipline, and a sense of civic duty. But other values will vary among different faith and family traditions. Each individual is free to chart his own sense of personal direction, guided and supported by his or her own mediating institutions. And that diversity is highly desirable—from it comes the pluralistic nature of a robust and open society. Only totalitarian states impose a single order of meaning on all of their people, overriding the free agency that would otherwise let people grow, develop, and contribute as they choose.

Clayton Christensen of the Harvard Business School faculty was talking recently with a Marxist economist from mainland China who was studying at Harvard. Clayton asked him, “What has surprised you most about your experience in America?” The man said he had been surprised to discover how crucial religion is to the functioning of democracy. “The reason democracy works,” he said, “is not because government [oversees] what everybody does, but because most people, most of the time, voluntarily choose to obey the law. In the past, most Americans attended a church or a synagogue every week and they were taught there by people they respected. Americans follow the rules because they believe they are accountable--not just to society, but to God.”41

Clayton said that this man’s insight heightened his personal concern that if religion loses its influence over the lives of Americans, “What will happen to our democracy? Where are the institutions,” he said, “that will teach the next generations that they too need to voluntarily choose to obey the law? If you take away religion, you can’t hire enough policemen.” 42

What does happen when mediating institutions don’t perform these civilizing functions? In totalitarian countries like North Korea and Iran, the state defines each citizen’s purpose, and imposes its will by force. At the other extreme is anarchy—supposed democracies, like some in the Middle East or Papua New Guinea, where people may vote, but violent crime, chaos, and poverty are everywhere. These countries lack the mediating institutions needed to teach people how to govern themselves.

In between these two extremes, I’m also concerned about the current decline of mediating institutions in the Western democracies—which, if not checked, could destroy our own stability and continuity. For instance, in the last fifty years, we have witnessed a significant weakening of the institutional family—the place where parents transmit the values of a civilized order to their children. I will note only a few headlines here, citing mostly U.S. data, which is typical of the trends in other developed Western countries.

Most Americans and Europeans today no longer think of marriage as a permanent social institution—that is, as a mediating institution. Rather, they think of marriage as a purely private and temporary source of personal fulfillment. So when a marriage becomes uncomfortable or inconvenient, marriage partners are much more likely to walk away—without considering the consequences of that decision on other family members, let alone the consequences for society. Since 1960 the American divorce rate has more than doubled--the U.S. is the world’s most divorce-prone country. And the number of couples living together without marriage has increased 15 times.43

Further, the percentage of children born outside marriage in the U.S. has increased from 5% to just over 40%, and in the U.K. from 5% to 47%.44 In Scandinavia now, 82% of all firstborn children are born to unmarried parents. The percentage of U.S. children being raised by single parents has quadrupled, from 8% to 32%. And among parents who have only a high school education, 70% of the children are now living in single-parent families. Why does this matter? Because the children of unwed, divorced and other single parents have three times as many serious behavioral, emotional, and developmental problems as children in two parent families— drug abuse, depression, violence, crime, and poverty. By every measure of child wellbeing, these children are far worse off than other children. And when that many children are dysfunctional, the entire society becomes dysfunctional.

As stated bluntly by a recent Time magazine article, “There is no other single force causing as much measurable hardship and human misery in this country as the collapse of marriage. It hurts children, it reduces mothers’ financial security, and it has landed with particular devastation on those who can bear it least: the nation’s underclass. The poor [have uncoupled] parenthood from marriage, and the financially secure [blast] apart their unions if they aren’t having fun anymore.”45

Recent research by Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam shows the effects of the marriage collapse on the many children in single-parent homes where the parent has only a high school education. Putnam’s typical but horrific case studies based on personal interviews put some compelling faces on the overall statistics:

For example, David grew up mostly with his dad, but he had nine half-siblings and no fixed address. “Adults moved in and out of his life without worrying what happened to the kids.” He went to “seven different elementary schools,” and school was “a problem,” but he still wants “a higher education” so he can get a job. He got his girlfriend pregnant, then she took up with a drug addict guy, but David still loves “being a dad.” He posted on Facebook, “I always end up at the losing end. I just want to feel whole again.”46

Kayla’s mom left her abusive first husband, lived with her boss for a while, and they had Kayla. Her mom then lived with several other men who drank a lot, but she never had a regular job. Kayla’s dad got an 18-year-old girl pregnant then left her when he found she was in an abusive relationship with her stepfather. So Kayla grew up with five step-siblings, saying her mom wasn’t “there for her.” She hated school and felt abandoned.47

When Elijah was a child he often saw “people being kidnapped and raped and killed.” He saw a child killed in a drive-by shooting when he was four. He didn’t see much of his mom but he visited his dad in jail. Once his dad beat him for burning down a lady’s house. Later his mom kicked him out of the house for getting “high and drunk every night.” He dreams of being a preacher, but he still “just love beating up somebody.” He’s got “a lot of personal issues.”48

From such stories and the extensive data behind them, New York Times columnist David Brooks has drawn the conclusion that, “We now have multiple generations of people caught in recurring feedback loops of economic stress and family breakdown, often leading to something approaching an anarchy of the intimate life.” In looking for basic causes, Brooks believes that the vital missing ingredient in these millions of families is not money or social policy; rather, the problem is the absence of “norms,” – the “habits and virtues” that determine a society’s health. For example, he writes, “In many parts of American there are no minimally agreed upon standards for what it means to be a father, There are no basic codes and rules woven into daily life.” And these norms “weren’t destroyed because of people with bad values. They were destroyed by a plague of nonjudgmentalism, which refused to assert that one way of behaving was better than another.”22

The “absence of norms?” Tocqueville called them “mores,” the “habits of the heart.” If they are missing, he said, democracy can’t function. So what’s wrong now? The key mediating structures of families and churches are growing weaker—unable to teach norms as they once did.

Other recent research has found—significantly--that family disintegration is strongly connected to declines in religious belief and practice. Mary Eberstadt’s book How the West Really Lost God: A New Theory of Secularization shows that family decline precedes and is a principal cause of declines in religious faith. Men who father children in a committed marriage, for example, are much more likely to become serious about spiritual values and personal responsibility. As George Gilder once put it, one hallmark of civilized society is when men learn from their women to identify with and take responsibility for their children.49

Drawing on data from both Europe and the U.S., Eberstadt finds that, “Religious practice declines dramatically alongside rising rates” of divorce, cohabitation, unwed births, and fertility decline. When family structure becomes disrupted, “many families can no longer function as a transmission belt for religious belief.” In addition, “people become insulated from the natural course of birth, death, and other momentous family events that are part of why people turn to religion in the first place.” Birth and death turn people toward religion? Is that because religion is a crutch—or is it because religion is the crux of what life is about?

Another factor that negatively affects the public’s current perception of religious influence is the conscious public relations strategy of some who portray anyone who disagrees with them as a bigot, rather than discussing freely the merits of their differences. As Elder Dallin H. Oaks said recently, these advocates are trying to crowd “religious voices, values, and motivations” from “the public square.” They do this by shouting down and boycotting those with religious values “on the [alleged] ground that they are irrational or that they reflect” hatred or bigotry, magnifying these allegations with rhetoric designed “to conceal or omit consideration of the very real secular reasons that support the position.50 Religion is [thus] being marginalized to the point of censorship or condemnation.”51

So here we are, having clearly established in the 800 years since Magna Carta, that civilized religion has played an indispensable role in creating and sustaining the freest democratic societies ever known. And yet democracy’s core values of civilized religion and religious freedom are now under siege—partly because of violent criminals who claim to have religious motives; partly because the wellsprings of stable social norms once transmitted naturally by religion and marriage-based family life are being polluted by complex social forces; and partly because the advocates of some causes today have marshaled enough political and financial capital to impose by intimidation, rather than by reason, their anti-religion strategy of “might makes right.”

It is true that those who value religion today cannot “lightly disown the influence of religion” associated with past intolerance and sometimes even hatred around the world today. As Robin Griffith-Jones and Mark Hill have said, “It may soon become harder to see any but the most diluted religion as a trustworthy ally in the defence of Western freedoms.”52 For that reason, those who understand the personal and social value of authentic, civilized religion now have a compelling need to oppose and remedy actual intolerance and hatred that claims to be justified by religion.

Religious believers must now articulate more clearly how it is possible to believe in role differences between fathers and mothers without being misogynistic, to prefer man-woman marriage without being homophobic, and to advocate moral norms without condoning violence toward those who disagree with them. At the same time, those who are hostile to religion should not disregard the influence of civilized religion in sustaining the very system that has allowed their own access to the public square.

Our current moment of celebrating Magna Carta comes at a time when some of its basic values are once more being threatened. This context calls to mind an even older yet similar iconic story from ancient England—the partly mythic tale of Camelot, King Arthur, and his knights of the round table. In the way T.H. White imagined the Camelot story, Arthur learned as a child from his teacher Merlyn exactly what King John learned at Runnymede—that it is wrong for a king or anyone else to use force to control other people. “Might is not right,” Arthur discovered. So, he continued, “Why can’t you harness Might so that it works for Right? Make it a great honour, you see, and make it fashionable and all that. Then I shall make the oath of [my] order [of knighthood] that Might is only to be used for Right…strike only on behalf of what is good…restore what has been done wrong, help the oppressed.”53

So Arthur founded Camelot, gathering 150 noble knights to the great round table, and for a time the idea worked. They used their might for right, fighting for the truth, helping the weak, and redressing wrongs. “The hope of making it” work, said Arthur, “would lie in culture. If people could be persuaded to read and write, not just to eat and make love, there was still a chance they might come to reason.”

But you know what happened. Personal weakness invaded their relationships, and Camelot collapsed in apparent failure. At the end of the Broadway version of T.H. White’s story, Arthur and his army are about to fight his former friend Lancelot in one more terrible battle. But at daybreak as Arthur is about to leave for the battle, he discovers a young boy, Tom of Warwick, who was so taken by the idea of Camelot that he had come to fight for the round table. Filled with new hope, Arthur talks to the boy, rehearses the ideals and the story of Camelot, and asks him not to fight but to return home and spread the story to any who will hear it.

Arthur speaks earnestly to Tom, “Merlyn . . . told me that a few hundred years from now it will be discovered that the world is round…like the table at which we sat with such high hope and noble purpose. If you do what I ask, [Thomas], perhaps people will remember how we at Camelot went questing for right and honor and justice. Perhaps one day men will sit around this world as we did once at our table and go questing once more, for right, honor, and justice.” 54

“Do you think you could do that, Thomas?” The child said with the pure eyes of absolute truth, “I would do anything for King Arthur.” “Will you remember that you are a kind of vessel, to carry on the idea, when things go wrong, and that the whole hope depends on you?”55 Thomas nods in solemn acceptance of his charge from the King.

Arthur says, “Give me the sword. Kneel, Tom, kneel. With this sword, Excalibur, I knight you Sir Tom of Warwick. And I command you to return home and carry out my orders.” “Yes, mi’lord,” says young Tom. Then Arthur’s fellow knight Pellinore calls to him, “Arthur? you’ve got a battle to fight.”

And Arthur answers, “Battle? I’ve won my battle, Pelly. Here’s my victory! What we did will be remembered. You’ll see, Pelly. Now run, Sir Tom! Behind the lines! Run!” Pellinore asks, “Who is that, Arthur?” “One of what we all are, Pelly. Less than a drop in the great blue motion of the sunlit sea. But it seems that some of the drops do sparkle, Pelly. Some of them do sparkle.”

I suggest that organizations like the BYU International Center for Law and Religion Studies, along with the other scholars gathered for this Conference on Religious Freedom at Oxford, are modern-day Toms of Warwick. And I believe that the central ideas of Camelot and Magna Carta, Edward Coke, John Milton, the American Founding Fathers, and Tocqueville are even more worth fighting for when they are threatened by warring factions who try to make us believe that no one can live up to such noble ideals.

It is time for another round table, one that gathers the knights representing the civilized world. Around this table we can discuss all of the issues on which reasonable minds can differ. We can each tell our own side of every story, without being shouted down or boycotted when our viewpoint differs from the others. I want the mayor of that Swedish city to know that this table will not include those who would take the lives of those who don’t accept their ideology. But I also want him to know that the table will include all those with differing—even intensely differing--views about almost everything else, from abortion and drug abuse and climate change to both secular and religious ideas about same-gender marriage—and the right of everyone at the table not only to speak to all others freely about their own beliefs, but also freely to exercise those beliefs in the way they conduct their lives. With society’s need for clear personal norms now so very high, we must not allow truly civilized religion to be rejected, marginalized, or belittled—lest we lose its civilizing force.

I close with Rudyard Kipling’s “Recessional,” his visionary plea from the 1897 diamond jubilee celebration for Queen Victoria, that we never forget under Whose divine care the democratic societies have developed into the free world as we know it today.

God of our fathers, known of old—

Lord of our far-flung battle line--

Beneath whose awful hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

. . . .

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe—

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard—

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding calls not Thee to guard.

For frantic boast and foolish word, Thy Mercy on Thy People, Lord!

Amen.

-

Obergefell v. Hodges, 135 S.Ct. 2584, 2607 (2015) (Kennedy, J., majority opinion).

-

135 S.Ct. at 2625 (Roberts, J., dissenting opinion).

-

Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, “The Great Charter at 800: Why it Still Matter,” First Things, January 23, 2015.

-

Lord Dyson, “Strengthened by the Rule of Law,” Magna Carta, Religion, and the Rule of Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015) (Robin Griffith-Jones and Mark Hill eds., hereinafter Jones & Hill), 334-335 quoting Lord Denning.

-

Jones & Hill, 5.

-

1 Samuel 10:24.

-

Jones & Hill 3.

-

Marshall Foster, WorldHistoryInstitute.com/magna carta.

-

John Witte Jr., “Towards a new Magna Carta for Early Modern England,” in Jones & Hill,113.

-

Ibid. at 116.

-

Ibid. at 134-35.

-

Sir Rabinder Singh, “The development of human rights thought from Magna Carta to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,” in Jones & Hill at 274, 280.

-

This is a paraphrase by Sir Rabinder Singh. Kennedy’s language was, “At the heart of Western freedom and democracy is the belief that the individual man, the child of God, is the touchstone of value. And all society, groups, [and] the state exist for his benefit.” Ibid. at 279.

-

Ibid. 280.

-

Ibid.

-

D&C 101:80

-

Wilford Woodruff, Conference Report, 10 April 1898, pp. 89-90, quoted in All That Was Promised, p. 307-08.

-

New York: Random House 2008.

-

Ibid at xv.

-

Ibid at 204.

-

Letter to Zabdiel Adams, June 21, 1776, Thefederalistpapers.org

-

Waldman at 186.

-

Ibid. at xvi.

-

Ibid. at 203.

-

“America’s Changing Religious Landscape,” Pew Research Center Religion and Public Life, May 7, 2015, www.pewforum.org.

-

Gallup reported 58% in 1995 and 56% in 2012 who said that religion is “very important in their lives.” www.gallup.com/poll/1690/religion.

-

Kevin Eckstrom, “Analysis: 5 Reasons Gay Marriage is Winning,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 22, 2014

-

Cathy Lynn Grossman, “Americans’ Confidence in Religion Hits New Low,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 17, 2015.

-

Waldman at 205.

-

Ibid. at 204.

-

Jones & Hill 17 (emphasis added).

-

Waldman at 187.

-

Ibid.

-

David McCullough, John Adams (New York Simon & Schuster 2001), 646.

-

Ibid. 647.

-

Democracy in America, (Mayer ed. 1966), p. 508

-

Ibid. at 291.

-

Ibid. at 292-93.

-

Ibid. at 294.

-

P. Berger & R. Neuhaus, To Empower People: The Role of Mediating Structures in Public Policy (1977).

-

Clayton Christensen on Religious Freedom, YouTube.

-

Ibid.

-

For data sources see Bruce C. Hafen, Covenant Hearts: Why Marriage Matters and How to Make it Last (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book 2008).

-

Office for National Statistics data cited in George Arnet, “More Babies Out of Marriage than ever Before—and what?” www.theguardian.com/news/datalog, 12 July 2013.

-

Caitlin Flanagan, “Why Marriage Matters,” Time, 13 July 2009, p. 45.

-

Robert D. Putnam, Our Kids (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2015), 26-29.

-

Ibid. at 56-60.

-

Ibid. at 104-108.

-

George Gilder, Sexual Suicide (San Antonio: Quadrangle, 1973).

-

Dallin H. Oaks, “Hope for the Years Ahead,” Center for Constitutional Studies, Utah Valley University, April 16, 2014.

-

See Stephen L. Carter, The Culture of Disbelief, (New York: Basic Books 1993), Ch. 11.

-

Jones & Hill at 18.

-

T.H. White, The Once and Future King (London: Collins 1958), 253.

-

Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner, Camelot Vocal Score (New York: Chappell & Co. 1960), 225-229.

-

T.H. White, at 674.